Notes from the 2012 Metathon, a weekend intensive on Dante’s Divine Comedy, led by Dr. Al Geier.

The Metathon ended Sunday night, complete with its traditional climactic cake. Lots of us stayed up an hour or two after eating to follow loose conversational threads from the last few days (“So what did you mean that knowledge is an image?”) or to play with our newly-minted inside jokes. It’s amazing the sort of work and play that’s possible after you’ve shared so many words and so much focus with a small group of loving people.

But there’s one discussion topic in particular that sticks with me. And that’s Satan.

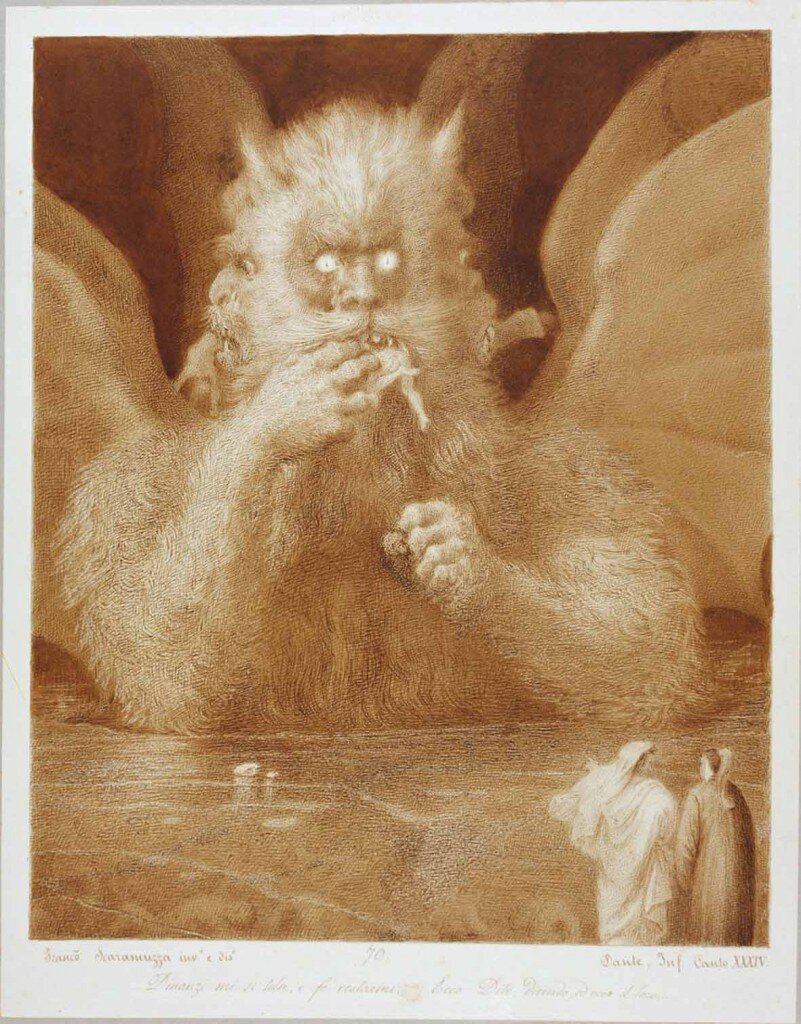

He’s immense and grotesque in Dante’s hell. Surrounded chest-high by ice that he creates by the relentless beating of his six scaly wings, he gnaws on the world’s three greatest traitors. Two faces grow on his shoulders, joined to the face at the front by their tops. Spit, foam, tears, and blood dribble off his chin. Bodies hang half-out of his mouth. We settled –pretty easily– on calling him a “freak.”

When Dante first sees him, he’s frozen by the sight:

How faint I then became, how turned to ice,

Reader, ask not; I will not write it down,

for any words I used would not suffice.

I did not die, did not remain alive.

Think for yourself, if wisdom buds in you,

what I became, deprived of life and death.

And it’s no wonder. Satan’s gruesomeness, his repetitive motions, and his massive size all end up being pretty hypnotic. They’ve become the frequent material for artists. They’re often considered the climax of the infernal story. They absorbed our conversation on Friday. It seems like just about everyone gets frozen with Dante, overwhelmed by the spectacle.

Everyone except for Virgil, that is. The guide God sent to Dante seems entirely unimpressed by the devil. Ever the tour guide, he tells Dante everything he thinks he needs to know, and he leaves Satan out of it entirely. He points out the three gnawed-on sinners, then says, almost dismissively,

…night is rising, and it’s time to leave,

for Hell has nothing more for us to see.

Satan doesn’t get a word of description from Virgil. This before the poet nonchalantly strolls up to Satan’s icky mass, counts the beats of his wings like a schoolboy waiting to skip into a double dutch game, grabs hairs on the devil’s side and climbs him like a stairway out of Hell, with Dante slung on his back. Satan just doesn’t seem to interest him.

And that is interesting. How could the prince of hell be boring?

Maybe Virgil had simply seen Satan too many times. Maybe he had a local’s forgetfulness of the value of his own environs. But that’s unlikely given Virgil’s reliability and his eagerness to describe so much of hell. And it’s absurd when you consider that after Dante is done with his initial, stunning view, he joins Virgil’s disinterest. He asks no questions about Satan, and he records no emotional response to the experience of approaching and climbing on him.

Dante’s response to seeing Satan couldn’t be more different than his response to seeing God. When he approaches “the source of every woe,” he’s surprised and stunned by an unexpected glance, he gushes description for a few lines, and then he runs out of things to say. Satan is all spectacle with no substance, like a badly-designed haunted house attraction. In contrast, Dante spends three books slowly preparing himself for the sight of God, slowly developing his capacity to see Him. Then, once he’s finally honed his eyes and language, he finds that his many, beautiful words are incapable of describing of the experience. He’d have to talk about it forever, and he’d still find the description inadequate.

Satan starts by overloading Dante, then turns out pretty vacuous. God slowly, slowly trains Dante, fills him up, transforms him, expands him, and then turns out to be infinitely greater than Dante is, even when Dante’s at his best.

I think Dante is right. Evil’s uninteresting. Satan’s uninteresting. They start with a hypnotizing bang, and then… that’s it. They’re done. You can describe evil, see its effects, and then climb its hairy flank back into the light of God’s sanctifying love.

We need, of course, to be careful here: it’s infinitely possible and often good to describe the injustice of horrors, and it’s wrong to neglect the pain of sin’s consequences, or the ability of devils to hurt people.

But seen next to God’s great goodness, there’s no comparison. No evil, devil, or darkness can compete with the patient splendor of our God’s majesty. His light exceeds speech, his mercy draws us close, and his love moves the furthest stars.